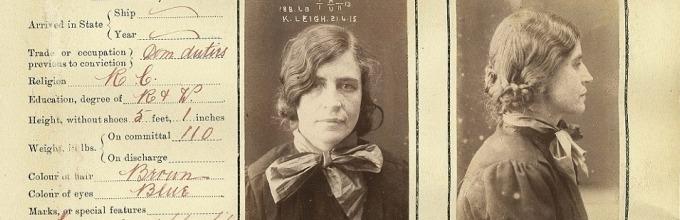

portion of Kate Leigh's police report, 1915

Dr Nicole McLennan, PhD ’98, detects deceivers in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, from ANU Reporter, vol 48, no 3, 2017, p 58

Barely a week goes by without an email from IT arriving in my inbox warning of phishing attempts and other scams.

As these ruses get more sophisticated, I have less faith in my ability to spot a fake from a genuine email. Yet, while their methods of delivery may have changed, it is worth remembering that fraudsters, quacks, confidence artists, hustlers and double–dealers are not a new phenomenon.

Some of Australia’s earliest arrivals from Europe were sent here after an unsuccessful demonstration of their skills in deception. For a few, it was these same talents that brought them success in the fledgling Australian colonies.

Among the most notorious was Francis Greenway (1777–1837) who, after being found guilty of forging a document, was transported to Australia and put his drafting skills to good use as an architect. He designed many of Sydney’s iconic early buildings, such as Hyde Park Barracks, but he made enemies and work was sparse in his later years.

Artist Joseph Lycett (1774–1825) was also transported for forgery. After arrival in Australia and a second conviction for forging five shilling bills, he was sent to the Newcastle penal settlement.

There he came under the supervision of Commandant James Wallis, an amateur artist, who encouraged Lycett to pursue his talent and helped secure his conditional pardon. Lycett completed many private commissions and landscapes before his return to England in 1822.

For some artifice was an ingrained habit. Murray Roberts (1919–1974) was a remarkable and charming impersonator. In his early twenties he began pretending to be medical doctor.

Among other things, he crafted false credentials to obtain work in the manufacturing and chemical industries, pretended to be Lord Russell to secure a hotel suite and wooed a widow out of four thousand pounds. Frequently before the courts, he told one magistrate that he was ‘more of a nuisance value than a criminal’.

Yet wealth was not always a motivation for deceit. During World War I air force pilot Cedric Hill (1891–1975) used his acting skills in a ruse to secure his release from a Turkish prisoner of war camp. He and Elias Jones, a Welsh prisoner, successfully faked insanity to fool doctors into approving their inclusion in a prisoner exchange.

Fakery has not just been the preserve of men. Fortune teller Julia Gibson (1872–1953) was convicted several times for deception. The crime entrepreneur Kate Leigh (1881–1964), while best known for making a fortune by supplying illicit goods, was also said to have aided other criminals by providing them with alibis.

Eugenia Falleni (1875–1938) who dressed as a man and lived as ‘Harry Leo Crawford’, was convicted in 1920 of the murder of her wife Annie Crawford. While it is not known whether Annie was aware that her husband was female, in the court it was claimed that Falleni had committed ‘sex fraud’ by impersonating a man and killed to hide the deception.

The most recent swindler to appear in the Australian Dictionary of Biography is John Friedrich (1950–1991).

He arrived in Australia in 1975 after defrauding a Munich company of 300,000 deutsche marks and faking his own death in a skiing accident.

Described as having a ‘hypnotic personality’, he rose to become director of the Victorian division of the National Safety Council of Australia (NSCAV). In this role he charmed politicians, secured government contracts, and borrowed large sums by persuading bankers that empty crates contained valuable equipment.

While he lived modestly, he used the funds to purchase helicopters, planes and ships, helping to boost both his and the organisation’s profile. By the time his deception was uncovered in 1989, the NSCAV’s debts amounted to approximately a quarter of a billion dollars.