Our king went forth to Normandy

Our king went forth to Normandy

With grace and might of chivalry

There God for him wrought marvellously

Wherefore England may call and cry

Thanks to God,

Give thanks to God, England, for this victory.1

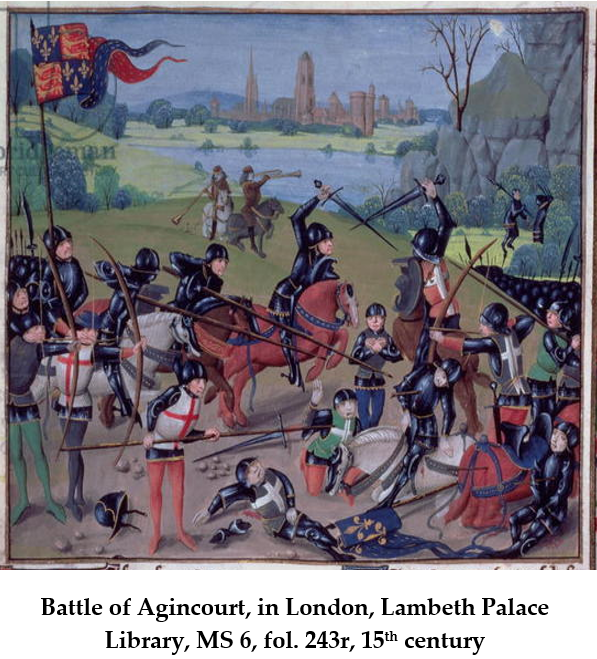

Thus begins a rousing song celebrating Henry V’s victory against the French at the Battle of Agincourt fought 600 years ago, on 25 October 1415. Evoking the chivalry of Henry’s army, and the heavenly agency that laboured benevolently for England, the ‘Agincourt Carol’ recounts the English king’s successful resumption of the Hundred Years War, his invasion of Normandy, and triumphant return to London later that year.

Henry ‘faught manly/ Thorow grace of God most mighty’ at Agincourt to win the day. The carol was one of a body of nationalist myth-making works that would see the victory at Agincourt become a symbol of the legitimacy of English political and military aspirations in later centuries. However, while God’s grace is reiterated as a significant factor contributing to Henry’s success in subsequent stanzas, chivalry, the elite ideology linking military prowess with Christian service and notions of honour, is not. Why is that?

Henry ‘faught manly/ Thorow grace of God most mighty’ at Agincourt to win the day. The carol was one of a body of nationalist myth-making works that would see the victory at Agincourt become a symbol of the legitimacy of English political and military aspirations in later centuries. However, while God’s grace is reiterated as a significant factor contributing to Henry’s success in subsequent stanzas, chivalry, the elite ideology linking military prowess with Christian service and notions of honour, is not. Why is that?

One reason may lie in Helen Deeming’s hypothesis that the carol was composed by clerics, whose focus on God’s beneficence towards Henry and England echoed the king’s own oft- and gratefully proclaimed acknowledgements of divine grace and favour. However, another reason may be the fact that Henry’s victory was not actually due to sensational acts of chivalry by his knights on horseback. Indeed, while Henry’s bold decision to initiate an attack on French troops was itself a significant factor contributing to his success, the English king also issued orders that transgressed contemporary standards of chivalric behaviour.

After substantial victories on the morning of Friday 25th, fearing a reorganization of French forces, Henry ordered that all non-royal prisoners be killed. This directive breached the widely held chivalric tradition that unarmed prisoners be protected (not least because they could garner a decent ransom for their captors!). French eyewitnesses report that English leaders resisted his command prompting Henry to order an esquire and 200 archers to slit captives’ throats and torch buildings in which injured prisoners had been incarcerated. While claims that thousands of French forces were executed in this way are not substantiated, hundreds of captives were put to death.

After substantial victories on the morning of Friday 25th, fearing a reorganization of French forces, Henry ordered that all non-royal prisoners be killed. This directive breached the widely held chivalric tradition that unarmed prisoners be protected (not least because they could garner a decent ransom for their captors!). French eyewitnesses report that English leaders resisted his command prompting Henry to order an esquire and 200 archers to slit captives’ throats and torch buildings in which injured prisoners had been incarcerated. While claims that thousands of French forces were executed in this way are not substantiated, hundreds of captives were put to death.

The ethics of the massacre at Agincourt have been widely argued, to the point of having been debated in a mock High Court trial in the US in 2010. However, military historians argue that we should not forget that along with the pressures of war informing Henry’s (as it turned out) incorrect assessment of French movements, chivalric ideology was in constant flux throughout this period. Notwithstanding, the ‘Agincourt Carol’, with its insistence on God’s grace, avoidance of chivalric flourishes, and selective detail, reminds us how triumphal propaganda successfully obscures both ambivalent military decisions and the deep human costs incurred by any war.

The ethics of the massacre at Agincourt have been widely argued, to the point of having been debated in a mock High Court trial in the US in 2010. However, military historians argue that we should not forget that along with the pressures of war informing Henry’s (as it turned out) incorrect assessment of French movements, chivalric ideology was in constant flux throughout this period. Notwithstanding, the ‘Agincourt Carol’, with its insistence on God’s grace, avoidance of chivalric flourishes, and selective detail, reminds us how triumphal propaganda successfully obscures both ambivalent military decisions and the deep human costs incurred by any war.

1For the Middle English text of the 'Agincourt Carol', see Luminarium: Anthology of English literature (accessed 30 Sept 2015).

*For more on the Battle of Agincourt and its 600th anniversary, see Agincourt 600.

Tania M. Colwell is a sessional lecturer in History at ANU specialising in medieval and early modern cultural history. She is currently teaching an honours-level course on Histories of Emotions in Premodern Europe.