Democratising the University

Democratising the University

In November 1959 a group of experts in education and economics gathered at The Hague under the auspices of the Organisation for European Economic Cooperation. The meeting’s title – ‘Techniques for Forecasting Future Requirements of Scientific and Technical Personnel’ - hardly sounded momentous. Nonetheless, the conference signalled a tectonic shift in attitudes towards tertiary education. In the coming decade an enormous wave of students entered higher education in Europe, transforming ancient, elite institutions into what contemporaries called the ‘mass university.’

Why expand higher education? The technocrats at the Hague conference argued for a direct link between the education of the workforce and economic growth. The long economic boom of the 1950s aided optimism in a sector where previously many feared the ‘overproduction’ of graduates. Education and research also lay at the heart of the cultural competition of the Cold War. In the shadow of the Sputnik shock of 1957, Europeans glanced nervously east and west at the Soviet Union and the United States, whose social systems, it appeared, educated both more and better. The early 1960s resounded with calls for expanding higher education in order not to collapse into intellectual underdevelopment.

The connection between education and economic growth provided the least politically controversial rationale for expanded university access. But others existed. The German sociologist Ralf Dahrendorf proclaimed access to higher education was a civil right. Others identified in an expanded higher education system the ultimate guarantor of social mobility. Many rejoiced that in an apparently endless economic boom, there no longer existed a contradiction between economic and idealistic reasons for opening access to the university. The demands of economics, equality of opportunity and social democracy had come together.

Thus in the course of the 1960s a new demographic entered the university. The extension of compulsory secondary schooling deposited many at the brink of higher education for the first time. A huge cohort who previously left the education system during or at the end of secondary education now went on to university. Women in particular formed a larger share of student enrolments, although decades would pass before parity was achieved. Contrary to the expectations, however, the new generations populated arts and humanities faculties rather than the fields of science and engineering. The mass university reflected not the economic and vocational vision of technocrats but the democratic demand of populations previously excluded from higher education.

If the new generation of students embodied the democratic aspirations of the post-war era, the universities they entered did not. Students found a curriculum premised on the presumption it served a small social elite. Despite the calls of technocrats, politicians rarely embraced an adequate financial provision of mass higher education. The expansion of education thus only highlighted the level of attrition in the university – in some instances calculated at up to 60% of the entering population. Poorer students, and those who had to work to support themselves, tended to fall by the wayside on the road of social mobility.

Many university administrations responded to overcrowding by proposing restrictions on entry. But the rapid retreat from the promise of education for all provoked a crisis. In November 1967, eight years after the Hague conference, students at the French university campus of Nanterre began a strike against university reforms that threatened their view of the democratisation of education. It ended in an ambiguous victory that left only dissatisfaction. The next revolt would be much more radical. In May 1968 events at Nanterre triggered a general strike in France and came close to toppling the government of General De Gaulle.

The revolts of the 1960s concerned a fundamental question of contemporary society. What should a democratic system of education look like? Despite the groundswell of support for mass education, the results were ambivalent. In Europe, student protest often succeeded in preventing any restriction on access to university. However, less success was had in ensuring the funding of higher education increased commensurate with the greater size of the student body. From today’s perspective, what is most striking is the strength of the vision of a democratic education, free and universally accessible, and, by contrast, the poverty of the contemporary political imagination.

Dr Ben Mercer is a Lecturer in the School of History and is particularly interested in the relationship between different forms of social, political and cultural change, including the history of reading, consumerism, the history of the university, of ideas and practices of democracy, as well as the representation and appropriation of the past for political purposes.

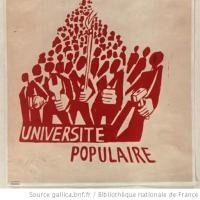

Image: French poster, 1968. “The People’s University”